By Linus Pott. Republished from the The Sustainable Cities blog.

More than 1,000 years.

That’s how long recent estimates suggest it would take in some developing countries to legally register all land – due to the limited number of land surveyors in country and the use of outdated, cumbersome, costly, and overly regulated surveying and registration procedures. But I am convinced that the target of registering all land can be achieved – faster and cheaper. This is an urgent need in Africa where less than 10% of all land is surveyed and registered, as this impacts securing land tenure rights for both women and men – a move that can have a greater effect on household income, food security, and equity.

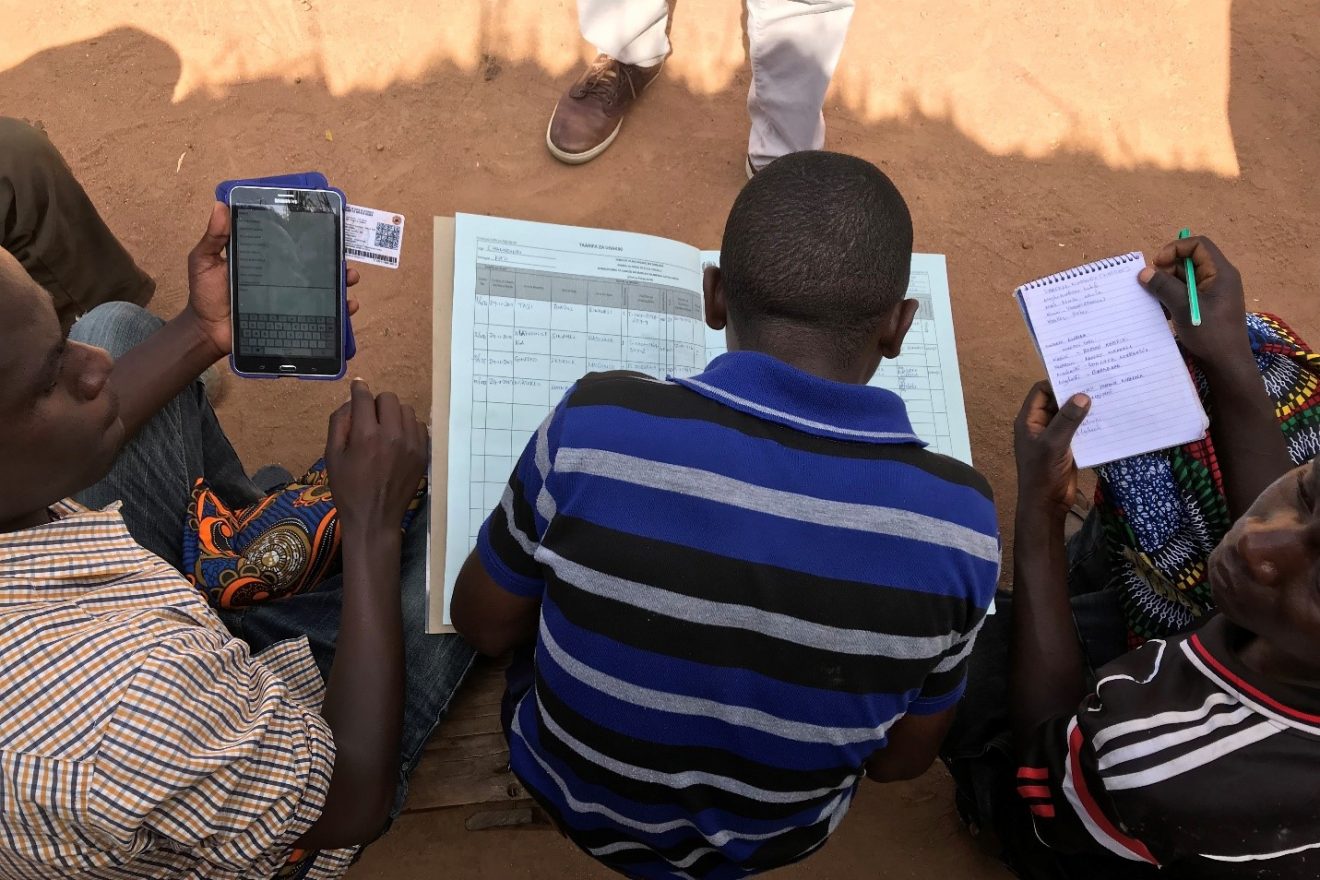

Perhaps one of our answers can be found in rural Tanzania where I recently witnessed the use of a mobile surveying and registration application. In several villages, USAID and the government of Tanzania are piloting the use of the Mobile Application to Secure Tenure (MAST), one of several (open-source) applications available on the market. DFID, SIDA, and DANIDA are supporting a similar project.

-

Photo by Linus Pott / World Bank A standard tablet or smartphone connected to a GPS receiver is used.

- In the presence of land rights holders and neighbors, community members are trained to use the application to record individual and communal land boundary and ownership information.

- Afterwards, a public display period for objection and correction is carried out to ascertain consensus.

- The data is automatically stored in a database once the device gains internet access – and when this is finally approved by government authorities.

Technology truly reduces the barriers to entry as it enables the participation of all community members – from the initial informational meeting to the confirmation of boundaries with neighbors, or as part of the team handling the application. Perhaps what was even more encouraging was the inclusion of youths and women in the teams, as they are often not given access to land and participation in land-related discussions in patriarchal societies and customary contexts.

Analysis shows that MAST has brought down the costs for issuing a Customary Certificate of Right of Occupancy, the legal certificate of securing tenure for customary land in rural Tanzania, to less than $10. While these costs exclude satellite imagery and technical assistance, they are still an indicator of how cheap mass registration can get.

While the technology is fit-for-purpose, a common concern is related to the lower accuracy of boundary demarcation conducted with mobile devices. However, in rural areas, surveying accuracies at the centimeter level are not always required, and a general boundary approach can be applied, since tenure security does not necessarily increase as the accuracy increases. Furthermore, new innovations, such as external antennas or smartphones with dual-frequency Global Navigation Satellite System receivers can be used for mobile boundary demarcation, which will continue to increase accuracy.

So how can we scale up these innovative technologies? As part of the World Bank’s Tanzania Land Tenure Improvement Project, a key activity will be to scale up the issuance of land certificates in rural areas. This will be the first time such technology is used on a large scale in Africa, and the lessons learned will be useful for other African countries embarking on land administration reforms supported by the World Bank – Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Liberia, and Mozambique.

It should also be noted that the usefulness of the technology depends on the context. In some cases, using the technology might require amendments of laws or regulations. And we are still exploring the question of how to adapt it to high-density urban areas.

Of course, technology is not the silver bullet for securing land tenure. It is very important to raise awareness of landholders on the processes and benefits of participation in the process and registration. Therefore, we need to create incentives for landholders to participate in land registration activities and make land certificates a desirable asset – for example, by linking them to access to (micro-)finance or agricultural inputs, developing alternative land dispute resolution mechanisms, and exploring innovative models for landholders to participate directly in negotiations with potential investors.

Also, land information systems and the geospatial infrastructure as well as policy and legal reform will be necessary for a systemic approach. Capacities to manage such reforms to secure tenure at scale are necessary as well.

Positively disruptive, don’t you think?